previous

next

Back

Advertising campaign from Smirnoff.

Teenager Ryan Furlong

'shooting' David Cameron.

(Getty Images)

MUSIC FOR SUPERMARKETS[1]

A conversation between Savage and Nav Haq

Nav Haq: Savage presents Jean Michel Jarre... An idea that you, shall we say, ‘appropriated’?

Savage: I remember we happened to meet in a bar in Berlin and we set about devising a fantastical new artwork; the aftermath of a Jean Michel Jarre concert, with lights, lasers, dry ice and other crowd generated debris. When the viewer arrives everything would already have happened. They would have missed the performance. This of course led to the grander idea of actually setting out to try and get him to come and play Spike Island, (which ultimately proved to be a somewhat heroic failure.) But at that point, in Berlin, I was more interested in the idea of the missed spectacle, and the potency of F.O.M.O.

N.H: F.O.M.O?

Savage: ‘Fear of missing out’, the internet generation phenomenon that's emerged alongside social networking. Are you attending? Yes/No/Maybe. It’s the new Facebook dilemma. The only way something seems valid is if it becomes memorable. To do so it has to attain visibility within social networking sites. People are now constantly looking for the next big thing and this is manufactured through generating a sense of expectation... of potential memories. The more that’s promised in these terms, the more likely that people will then go and attend that event, simply for fear of missing out. So the pressure is to perform, to deliver, for fear that the fear of missing out isn’t generated. One has to be ever more spectacular. Which brings us straight back to Jarre, the progenitor of the modern day spectacle. How perfect would it be to bring it full circle? To get the legendary 80s electronic synth-pop icon in to do a show... as art?

N.H: Well, recorded music doesn’t really cost anything anymore so the way the industry generates value is through the live event.

S: Yes, the economics of music have shifted to the economics of experience and that’s very much a ‘noughties’ trend. You just have to look at something like Smirnoff's 'Nightlife Exchange' and 'Be There' campaigns[2], all promoting unique, live experience.

N.H: Where do you think your interest in experiential situations has come from?

S: I’m interested in looking at trends, in patterns of behaviour. My primary interest is in social value systems, whereby we see fashion influencing how people actually value things. Value has shifted away from being solely about commodities, even though they’re obviously still desirable. People now want value-added, they want a memory. If there’s a memory, there’s greater sense of validation. If you can remember where you have been with someone there’s shared experience, which has perhaps greater value than the isolated experience. If you’re alone, you have no one to prove you were there. However if you can share your experience with somebody – ‘”Were you there?” – “... yeah, I was there, it was great wasn’t it?” – “Yeah, it was REALLY great”’, it means that there is a greater sense of self-actualisation, of purpose in a purposeless world where basically everything has been geared, since Thatcher, to being completely and utterly embedded in materialist profligacy, and evidencing that through conspicuous consumerism. So my interest in the experience economy comes from how we have been manipulated as consumers.

N.H: For a while I’ve been interested in retail concept stores like Nike Town or the Apple Store, where commerce meets theatre and where there is obviously a real sense of coercion, in that you are made to feel that you’re a kind of a protagonist and a creative person. So when you go into Nike Town you can design your own shoes, you can pick a red swoosh with blue laces, and you can have your name put on your trainers, so you’re individualising them. It’s about privileging the subjective. In principle at least, it’s supposed to be about giving each individual person a different experience.

S: I remember when I first walked into Nike Town. There are four floors dedicated to trainers and sport, and I just went “Hallelujah”. It’s almost a religious experience ... it certainly feels designed as one.

N.H: What I find curious about that type of architecture, this being very much the positive perspective of those kinds of places, is that you can’t quite tell what their influences are. As when John Peel would play The Smiths and say that they were the only band whose influences you couldn’t identify. With this kind of architecture there’s no essentialism. You can’t necessarily see that it’s inherited from modernism. It’s like a whole other kind of postmodern space that doesn’t necessarily relate to anything that’s come before it.

Do you think these places are deliberately designed so as not to detract from a ‘unique’ consumer experience, for each individual?

S: Those situations are very much about retail as theatre. The products themselves become a souvenir or a prop, and you’re charged more for the pleasure. Often you’re buying into a lifestyle, as it were. I’m particularly interested in how this relates to the museum or gallery context which is clearly learning a lot from these places and from the concept of the ‘experience economy’ by becoming more experiential in similar ways.

S: Do you think galleries and museums are under pressure to keep up with this need to entertain?

N.H: On one level yes, because they have to fulfil the requirements of being recognised public institutions, which means they have to attract an ever-increasing number of visitors. There is also an economic imperative – the more visitors, the more organisations earn through sales of coffee and postcards and so on. There are definitely principles passed from one to the other. Its come full circle, because I think concept stores have similarly learnt a lot from what the historical idea of what a museum is. In a sense they are quite museological and even educational. If you go to Nike Town you learn about how they make their footwear and the history of Nike.

S: So these massive global brands become educators in the same way museums do?

N.H: Well in theories of the experience economy, which is now more than ten years old, it is referred to using the horrible neologism ‘edutainment’. It’s educational but tries to be so in a way that's not educational in the pedagogical sense.

S: Sir Ken Robinson, the educationalist, has clearly articulated the failure within education to respond to the demands of a contemporary and pluralist society. Our education system is built on the Victorian model. Is edutainment a response to this? Is this what we buy into now? I Didn’t Know Anything Before and I Still Don’t Know Anything Now is pathetic in its dedication to knowledge, as it expresses the idea that there is so much that is inherently useless. Who really needs a beginner’s guide to sex in the afterlife or nation building?It’s absurd that we are blindly pursuing the virtues of education, yet have accumulated so much useless knowledge already. I think it’s wrapped up with all these false promises, the false promise of commodity, of education and of celebrity or fame. That runs through the whole exhibition at Spike Island right from the beginning with my application film which says ‘I’m going to get Jean Michel Jarre to come and play in Bristol, it’s going to be great...’ and obviously none of it happens, it’s absolutely a false promise.

N.H: I have always understood I didn't know anything before and I still don't know anything now work as being about neo-liberal culture, where you are persuaded to become more reliant on yourself as an individual in society and you have to be entrepreneurial.

S: Absolutely! It's about the democratisation of ambition. With the levelling of every book to a single horizon line, there is a romantic vision presented of 'anything's possible.' All this potential and inevitable failure and futility in, as you just said, self reliance.

N.H: I Asked You a Thousand Times repeatedly delivers the same line 'What do you want from me?' This is set against the work You Will Have What You Want Sometime Soon. They both make use of the word ‘want’ and clearly state something about desire and consumption.

S: We have grown up for generations thinking that we can have what we want, we’ve grown up with that materialist expectation, yet now all of us are realising that we can’t have what we want, because it simply isn’t economically sustainable. That false promise that is Nike, that is Apple, the way in which these global brands represent and circumscribe notions of liberty, freedom, idealism, all those neo-liberal ideals, this image doesn’t equate to reality. The recent riots across the UK are testament to very real cracks in the social fabric.[3] Where once we were led to believe it was or would all be ours, now it clearly is not and will not be. We are becoming economically atomized with generations completely disenfranchised from basics like housing and education. You can either better yourself through education, become famous or buy yourself happiness. And moreover we want all this to have meaning and we’re led to believe we can find it all through Life Inc.

N.H: So do you think we are coerced into craving experiences? Or that experience becomes standardised?

S: How can they be anything but? Advertising has always been known to distort the truth. Now we have reality itself being manipulated. We’re on a real life Disney ride. It's coercion to the point of being sinister, yet it’s fascinating. You can't help but admire the way that Nike sells individualism through experience. We all know it’s utterly engineered, in the same way that we all know we’re being manipulated by Apple. I'm sure that this phone we’re recording this conversation on could be designed to be completely finger mark free, however what they’ve done is to make sure that it isn’t, so you’re constantly polishing it against your trouser, your shirt, your jacket and so developing some sense of emotional relationship to that product, which is completely brilliant design thinking.

N.H: The way you talk about the i-phone, suggests a need to rethink our relationship to objects. From a very young age your teddy bear becomes a comfort blanket on which to project and develop your own personality. I think that a lot of technology products for adults, such as ones by Apple, try to set up a contemporary equivalent of something like this. They try to become an extension of your mind as well as your body, and you start to hate situations when they’re not to hand.

S: Exactly, we know that we’re being manipulated by object design...there is this whole cult of product and product experience. Yet going back to Jarre – when I was eighteen years old in London Docklands listening to him blasting out that electronic-synth pop while thousands of pounds worth of fireworks exploded all around me, it blew my mind. What is going to be the experience of tomorrow? Where is this all going to go? Is it ever going create the same kind of impact that it did way back then? I think it will, it somehow always does.

N.H: There have been attempts in art. For example with those spectacular commissions in the Turbine hall at Tate Modern. I think that The Weather Project by Olafur Eliasson was quite interesting because it was all theatre. It was incredibly memorable and people loved it, yet in the context of his own work, it was kind of dumb.

S: That’s what we’re talking about – the fact that the experience is engineered, the spectacle is the manufacture of memory, and therefore of F.O.M.O. As long as you can manufacture memory then that is where the value lies.

N.H: That’s what I mean when I say these ideas are now entering the world of contemporary art as well. I’m very curious about the effect that the experience economy has on the making of art and even our readings today of historical art. When you go to a museum, is seeing historical artwork different today than it would have been twenty years ago, because of this new theatrical context that’s created for it?

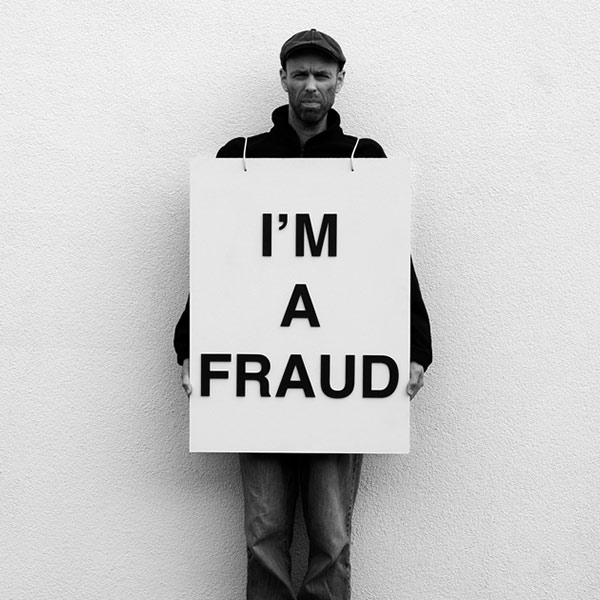

I'm A Fraud (2010)

S: If reality becomes ever closer to that of a Disney ride it will simply become a prop to mediate information appertaining to what you will walk away with in terms of memories, more ‘infotainment’ than art in its own terms. Whether it's in a gallery, a museum or a shop it would appear to be completely inflected by the experience economy. The contents fading into the background over the need to deliver memory making user friendly environments whereby people will 'naturally' find themselves buying trophies in the adjoining gift shop. Take the Disney Store itself - perhaps the original corporate master of escapism. From the outset it is a script, a performance. Without fail whenever you walk in you will always have some poor 'cast member' who is obliged to smile and say hello to you. You just know in reality that would never happen.

[1] Music for Supermarkets (Musique pour Supermarché) is the title of an album by Jean Michel Jarre from 1983. Jarre was asked to compose the background music for a supermarket themed art exhibition. The exhibition was at the Jean-Claude Riedel Gallery, Paris, between June 2 and June 30 1983 and the work on display was to be auctioned off afterwards. Jarre decided that the music accompanying the exhibition was a unique work of art as well and that he would have only a single copy of Music for Supermarkets pressed and auctioned for charity. All master copies were destroyed, leaving only one copy in existence.

[2] Smirnoff’s advertising campaigns are in the business of generating 'cool' around their product. ″Nightlife Exchange″ is, according to their website; ″A cross-pollination of nightlife around the world creating an iconic, global THERE moment.″ The ″Be There″ campaign shows us happenings of underground cool from a secret fancy dress party in a forest to a spontaneous gig in a subway. Many of these adverts asked us 'When was the last time you said...you were there?'

[3] Teenager Ryan Furlong 'shot' David Cameron on a housing estate in Manchester back in 2007. This now infamous picture is perhaps clear sign that a gap was already yawning between the young and disenfranchised and those in power. Cameron took coalition power in 2010. With swathes of cuts announced soon after, the gap apparently widened. A year later riots broke out all across the UK. During the riots comments on Twitter provided startling cynicism: One Tweet read 'Arab Spring - Basic Human Rights; UK riots - 42" HD ready plasma'. Following the riots, in her speech to the Commons, Home Secretary, Theresa May admitted there was 'something very deeply wrong with our [British] society'.

This interview was first published in the exhibition catalogue Savage presents Jean Miche Jarre in 2012.

Nav Haq is Exhibitions Curator at the M HKA, (Museum of Contemporary Art) in Antwerp. Haq writes regularly and has contributed to magazines including Frieze, Bidoun and Kaleidoscope.