The Fantastic Form of a Relation Between Things

Stephen Duncombe

I’ve started this essay on Savage’s work a dozen different ways but I always return to the same point: Marx. Not the angry revolutionary who excoriates the bourgeoisie and exalts the proletariat as he lays out the inevitable course of history. Savage doesn’t point fingers and there are no sides to take, nor is there any clear vision of an alternative future or a political path that might take us there. Yet it’s not the analytic Marx that Savage reminds me of either. There’s nothing in the artist’s work that translates into the mathematical certainties of the laws of surplus value and the attendant Enlightenment delusion that simply knowing the truth – the right equation – will set you free. Savage is a romantic, not an academic, and his aim is to dramatise more than analyse. Still Savage reminds me of Marx. Marx the keen observer. Marx who noticed something mysterious and new being born within Capitalism: the commodity.

The commodity, as Savage understands, is something greater than a mere product: it is a living thing. As Marx writes in Capital:

"It not only stands with its feet on the ground, but, in relation to all other commodities, it stands on its head, and evolves out of its wooden brain grotesque ideas, far more wonderful than if it were to begin dancing of its own free will."[1]

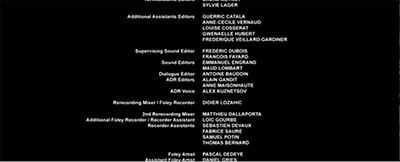

As the commodity comes to life it takes on a phantasmagoric quality. An inert object is animated: it dances for us and tells grotesque stories about itself and what it can do. A pair of Nike trainers is never something you just wear on your feet; they contain all the dreams and aspirations developed to accompany them. This phantasmagorical presence of the commodity is the replacement for an absence. Every commodity holds a “secret”: its true nature. Commodities, at their core, are about people: people make them, people exchange them, people consume them. But when we encounter the commodity this intricate web of human interdependencies disappear. Brands and advertisements identify and define the products that define and identify us, and the essential humanity of the commodity is overlooked. Savage’s Requiem (2011) reminds us of this. There is no main feature, only endless rolling credits listing the people responsible for making the things that make up our life …and no one bothers to stay around to watch.

Requiem (2011)

Savage picks up where the project of Capital and Marx’s analysis of production left off. Marx looked through the commodity backwards, searching for the hidden labour behind it. Savage projects forward: dramatising the complicated relationships we have with commodities and, more to the point, the complicated relationships we have with one another, and ourselves, through commodities. With a list of borrowed things, (or things presumably borrowed), Savage charts an index of associations in an earlier work: All that is not mine (2006). Each commodity becomes a marker of someone he has known, or forgotten, or never really knew in the first place. The relationships recede as the commodities remain, yet traces of people are still there. In another series of interventions products are picked up, repaired, put back and then picked up again by others. Through this project, Savage traces the circulation of commodities not as economists such as Marx usually consider the process, that is, from production through consumption, but instead what takes place after the initial purchase. This is the after-life of commodities: their travels in the wake of the legitimate economy.

Some of Savage’s art actions have an apparent altruistic quality. In Keeping Things Just Tickety-Boo (2003) a blanket is found, cleaned and then left for another to find: a good deed done. Yet behind this veneer of good works is a more questionable ethics. Was the blanket ever really abandoned? Or was the original owner on their way back to retrieve it when Savage spirited it off? And the person who finds and takes the item once it has been replaced, how are they implicated? Are they the innocent, fortunate recipient of this anonymous act of good citizenship or, ignorant of the entire process that precedes their discovery, are they really just a petty thief? Or consider Savage’s communication with strangers about a missing car mirror. Is the card he tucks under a stranger’s windscreen wiper informing them “I have your wing mirror” a helpful message, or a ransom note? Savage’s work is neither moral, nor immoral; rather it is a dramatization of everyday human interaction acted out through the commodities we buy, borrow and steal, find, lose and own. As Marx writes:

"It is nothing but the definite social relation between men themselves which assumes here, for them, the fantastic form of a relation between things.”[2]

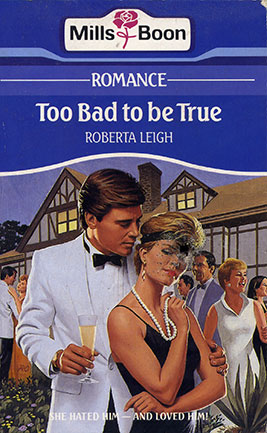

Commodities are not, however, things alien to or outside of us, and this is especially true at a time when more and more of the economy is geared toward the production and consumption of informational and cultural goods. We become the commodities we consume and, as we see ourselves through our choice of commodities, we begin to understand ourselves and our experiences as commodifiable. Thus Savage has highlighted in I Didn’t Know Anything Before and I Still Don’t Know Anything Now (2011) that we potentially read How-To Guides in the same way we watch advertisements, seeking the promise of a miraculous transformation of ourselves into something better and more desirable. In Now Look What You Made Me Go And Do (2010), he proposes how our fantasies of a life of romance may also be shot through with competing fantasies of violence (literally in this case). It is as if we are constantly on stage with the audience murmuring around us. Will they applaud? Will they appreciate the packaged self we have created for them? Or will their recognition come too late? In answer to these questions, the artist suggests that perhaps You will have what you want sometime soon (2011)… but never right now.

Which brings us to Jean-Michel Jarre. Why do thousands upon thousands of people flock to his concerts? It’s not just to listen to his music, or to see his fireworks and light show. As with all spectacles we go for the promise of something, something that will happen, something bigger and more meaningful than we’ve been sold. In other words, we are waiting for the commodity (for a spectacle is nothing more than the commodity form as a performance) to deliver on the fantasy it has promised. It never does. What arrives is us: the spectators, but with our eyes fixed to the object out front so we don’t even notice we’re here, unless we appear, for a brief moment, on the venue’s supersize video screen. By publicising Jarre’s appearance when he knows he’s not going to come, Savage strips the spectacle down to its bare form. He delivers the promise, and nothing more. Savage gives us nothing…except ourselves, here, now.

What do you want from me? Much has been said and written about the English rioters of August 2011: who they were and what they wanted. From the Right the answers to these questions are found in character. The rioters, in Prime Minister David Cameron’s words, are “immoral,” or representatives of a “feral underclass” as Kenneth Clarke,Secretary of State for Justice, rather more emphatically stated. The Left, predictably, blames society: the rising disparities between rich and poor, the government’s austerity programs, and so on. The rioting youth are expresseding their alienation from and anger with the State that wants nothing from them and couldn’t care less what they want. There’s a partial truth to both sides, for what we witnessed in August is the angry manifestation of a character type with deep roots in our present society: the rebel-consumer. While the youth in the streets of other nations around the world demand an end to dictatorships or march for an equitable distribution of wealth, Britain loots the local Foot Locker. Marx’s productionist plea “Workers of the World Unite” has been replaced by the consumerist call “Let’s Go Shopping!” albeit expressed in its most radical form: without money or permission.

Confronted with this seeming failure of revolutionary subjectivity, it is understandable to want to turn the clocks back to a time before our lives were thoroughly commodified, when workers armed with a productionist ethos and militant class consciousness offered the credible promise of a different type of world. Or, we might imagine a great leap forward to a future Utopia, an autonomous zone where we can live, magically, outside the circulation of commodities. Perhaps instead we pledge ourselves to live “the simple life” in the present, swearing off the commodity by “doing more with less.” But these are all fantasies, no less alluring and no less empty as those offered up by consumer capitalism.

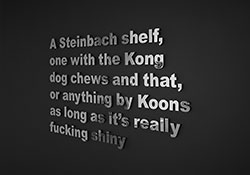

Steinbach vs. Koons (No 3 in The Fucking Cool Series)(2010)

No doubt our world needs changing, and Savage’s art tells us why: social relationships have become relationships between and about things. Yet what could be a depressing conclusion really isn’t, for through his work the artist reveals the commodity for what it is: a human product, of labour, yes, but also of desire and delusion, cooperation and selfishness; of lives alienated but also shared. Lying just below all that Really Fucking Shiny stuff are rough and gentle human ties. This is where I see a possibility for what I want: a more human-centered society. But Savage reminds me that to get there we need to start here. Maybe we will have what we want sometime soon, but we’ll need to work within and through the commodity form and our commodified selves if we ever hope to get to the other side.

[1]Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1, Ben Fowlkes, trans., London: Penguin/New Left Review, 1867/1976, pp.163 - 164.

[2]Ibid p.165.

This essay was first published in the exhibition catalogue Savage presents Jean Michel Jarre in 2012.

Stephen Duncombe is an Associate Professor at Gallatin School, New York University where he teaches the history and politics of media. He is the author of Dream: Re-Imagining Progressive Politics in an Age of Fantasy and writes regularly on the intersection of culture and politics for a range of scholarly and popular publications,from the cerebral, The Nation to the prurient, Playboy.

Duncombe is a life-long political activist, working as an organiser for the NYC chapter of the international direct action group, Reclaim the streets. He co-created the School for Creative Activism in 2011, and is presently the co-director of the Center for Artistic Activism.